PROJECTS

The face recognition game

Letting people explore what parts of a face are important for a face recognition system by making them wear funny masks.

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: Running the game at KI&Wir Magdeburg

- Part III: Technical details of the implementation

The following text presumes that you have read Build a Hardware-based Face Recognition System for $150 with the Nvidia Jetson Nano and Python or are already somewhat familiar with face recognition.

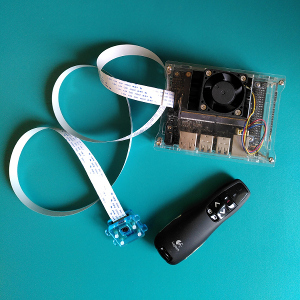

Hardware

Here’s what is needed to run the game:

- External display or TV

- Nvidia Jetson Nano, with fan installed

- 5V/4A power supply (see Jetson manual)

- Raspberry Pi V2.1, 8 MP 1080P camera

- Helpful: longer camera cable

- Keyboard or presentation clicker thingy (provides the “Please register me” button)

Except for the screen (hopefully provided by the venue), everything fits into a tiny bag, perfect for traveling to conferences and similar events. Another big advantage of this setup is that everything runs offline, avoiding potentially shaky internet connections as well as privacy concerns.

Both the fan and the external power supply (as opposed to the standard USB power supply) ensure that the system can keep running at full power for a long time (longest I tested was ~6 hours, zero issues with the hardware observed).

Face recognition models

The original blogpost uses dlibs HOG-based face detection model. While that model works very well when the person looks right into the camera, it has a lot of trouble detecting faces that are turned sideways to the camera, severely limiting the usability of the game. Instead I opted for dlibs CNN-based face detection model, which performs strong on both frontal as well as sideways faces (see here for a detailed comparison of different face detection models).

I also switched out the feature extraction model originally used in the tutorial for openface (for reasons that now unfortunately elude me).

Speeding it up

With a camera resolution of 1280x720 pixels and 1000 people registered in the face database, the face recognition takes roughly half a second per image (95% confidence interval: [0.479,0.482] seconds). The bulk of the processing is face detection (performed on downscaled 640x360 pixel image, on average 0.24 seconds per image). If more than one person stands in front of the camera, the total processing time increases by about 0.1 seconds per additional person (cropping and face-matching scale linearly with the number of persons, face detection and feature extraction are the same regardless of the number of persons).

With at most two processed images per second, running face recognition in the same process as the camera+display routine would make for an unusable game. The image displayed would only be updated twice per second and would be running behind the actual user movements considerably. Such a low-framerate and long delay is very noticeable and extremely irritating to users.

Instead, I parallelized the game as follows: The main process takes care only of grabbing the image from the camera and displaying on the screen (at a framerate of 25 frames/second). The recognition process receives images from the main process and returns the recognition results when finished. The main process only sends new work to the recognition process when the previous recognition is done. I initially tried to parallelize using threads rather than processes, but fell prey to some global lock somewhere in the depths of opencv.

In effect, at a framerate of 25 frames/second, the camera+display is fast enough to mirror the user’s movements. Recognized face locations and matches are only updated roughly twice per second, i.e. the face bounding boxes might be out-of-sync by up to half a second. While this is slightly annoying, it is considerably less so than the out-of-sync camera image in the single-process implementation.

Explicit registration

Rather than automatically adding people to the face database the first time they look into the camera, I opted for an explicit registration process: anybody that wants to play the game has to look right into the camera and press a button to add their face to the face database. The reasons for this choice were twofold:

1. Automatic registration resulted in people being added to the database multiple times, e.g. once without a mask, once wearing a mask. It was not possible to find a combination of thresholds that reliably distinguishes between “this is genuinely a new person” and “this is a known person but currently wearing a mask”. During test runs, automatic registration resulted in situations where visitors would be matched with multiple versions of themselves, which caused significant confusion for the visitors.

To get explicit consent of visitors to store their personal data (something that several visitors indeed enquired about).

Source code

The source code is available on github.

home

home